Updated this thread with the full debate articles for whomever interested. This is now a very long thread with a lot of actual vaping advocacy information presented.

This first post is the original news article as it appeared, the second post is the news article response from the Bloomberg crowd and the third post is the anti counter news article response back to the Bloomberg crowd basically telling them they have have no idea what their talking about with actual facts presented and to stop lying to all of us. Priceless!

https://web.archive.org/web/2021032...gainst-vaping-could-it-do-more-harm-than-good

Bloomberg’s Millions Funded an Effective Campaign Against Vaping. Could It Do More Harm Than Good?

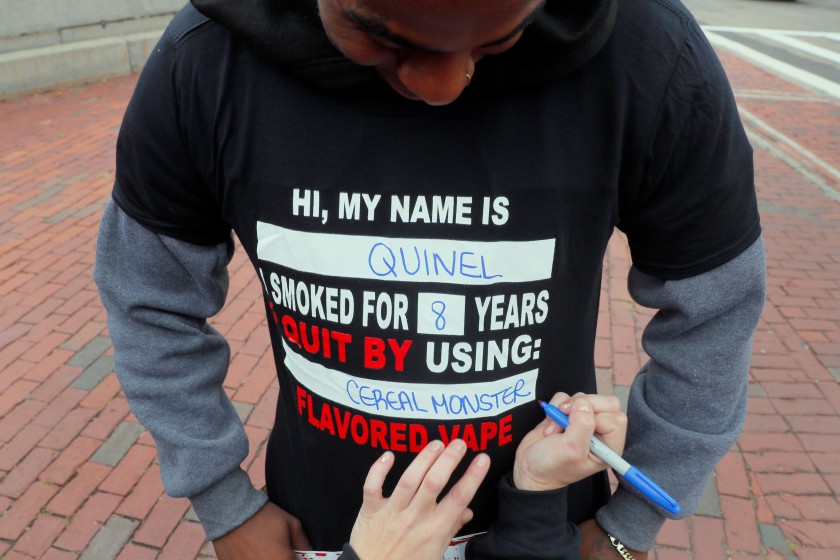

Public-health experts say that e-cigarettes play an important role in getting people to stop smoking.

STEVEN SENNE, AP

The widespread use of e-cigarettes by teenagers declined after a campaign led by Michael Bloomberg and Tobacco-Free Campaign Kids.

GIVING

By Marc Gunther

MARCH 23, 2021

In September 2019, Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire philanthropist, and Matthew Myers, president of the nonprofit Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, unveiled a $160 million, three-year campaign to end what they described as an epidemic of e-cigarette use among kids.

In a New York Times op-ed, Bloomberg and Myers attacked Big Tobacco for putting young people in serious danger by hooking them on addictive e-cigarettes, which are sold in kid-friendly flavors like cotton candy and gummy bear.

Backed by a coalition of influential nonprofits, including the anti-tobacco Truth Initiative, American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, and American Lung Association, they called for a national ban on flavored e-cigarettes.

Bloomberg lamented: “All the progress that we’ve made in reducing teen smoking is being turned around.”

Their timing was propitious. A year earlier, the FDA and the U.S. Surgeon General declared youth e-cigarette use an epidemic. Fears were mounting about unexplained deaths linked to vaping. A few cities, including San Francisco, had banned flavored e-cigarettes. Michigan had just become the first state to do so.

What Philanthropy Is Accomplishing

This is part of a Chronicle series taking a deep dive into the results of big philanthropic efforts to discover what has worked, what has failed, and what donors can learn.

In the months that followed, five more states — California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island — banned flavored e-cigarettes. So did several big cities, including Chicago and Philadelphia. Congress raised the federal minimum age of sale for all tobacco products from 18 to 21. Anti-vaping messages dominated the national conversation.

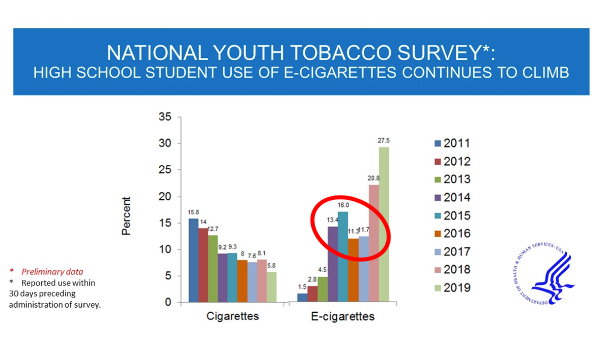

All of this had an impact: The use of e-cigarettes by middle-school and high-school students declined sharply from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I think it’s fair to say that Bloomberg’s funding has produced measurable, significant results,” says Myers, a founder of Tobacco-Free Kids and a longtime leader in the fight to curb tobacco use.

Seen in that light, the work of Bloomberg Philanthropies and Tobacco-Free Kids looks to be an uncomplicated story of philanthropic success.

It is anything but.

Bloomberg Philanthropies used its money and influence to curb vaping, to be sure. But others who have worked for decades to reduce deaths from smoking say the ongoing campaign against e-cigarettes is misguided, built on unsound science and likely to do more harm than good.

Less Dangerous

Kenneth Warner cares about tobacco control as much as anyone. A founding board member of the Truth Initiative — the nonprofit public-health organization committed to ending tobacco use — Warner has also been the president of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, the senior scientific editor of the 25th-anniversary Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health, and the dean of the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Kenneth Warner, a University of Michigan scholar, says harm from tobacco is far greater than from vaping: “Michael Bloomberg had sone great things for public health, but he is way off base on this.”

Years ago, Warner and a colleague, David Mendez, built a computer model that tracks the U.S. adult population’s smoking status and smoking-related deaths. When they ran data about vaping through the model, they found that under all but the very worst-case assumptions, the benefits of e-cigarettes, which can help smokers quit, exceed their costs in terms of lives saved. Warner says the campaigns against e-cigarettes are a mistake.

“Michael Bloomberg has done great things for public health,” he says. “But he is way off base on this.” Other respected elders of the tobacco-control movement share that view.

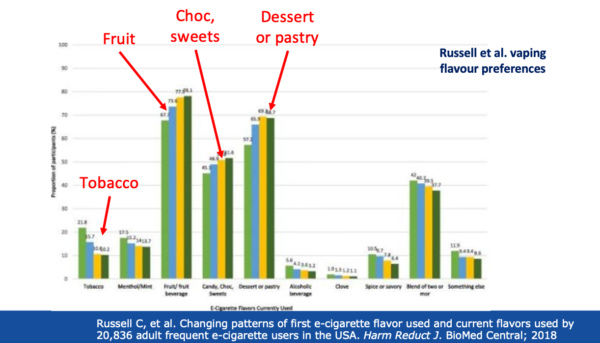

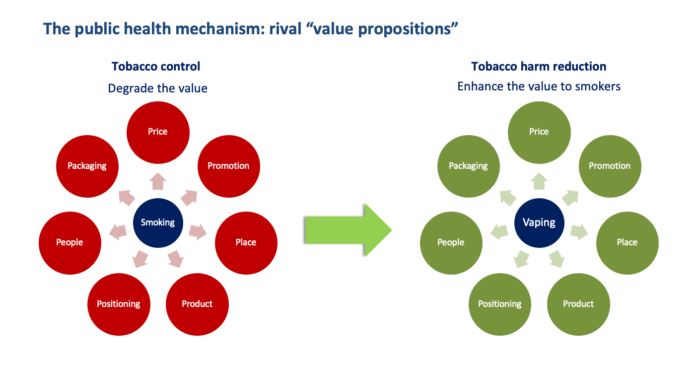

The critics’ argument goes like this: While e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco both contain nicotine, an addictive chemical stimulant derived from tobacco, e-cigarettes are much less dangerous than smoking. Vaping appeals to smokers who want to quit but need a nicotine fix. Like kids, adult vapers prefer flavors. So while no one wants teenagers to vape, removing flavored e-cigarettes from the market deprives adult smokers of a popular safer alternative.

ADVERTISEMENT

Worse, the critics say, by exaggerating the dangers of e-cigarettes, Bloomberg, Myers, and their allies have inadvertently given people a reason to smoke. Public opinion polls show that Americans overestimate the risks of vaping.

In “Evidence, Alarm and the Debate Over E-Cigarettes,” an essay in the journal Science, five public-health experts write that it’s a mistake to restrict access to vaping products while leaving deadly cigarettes on the market. The authors include Cheryl Healton, the former chief executive of the Truth Initiative, who is dean of the New York University school of public health, as well as the deans of the schools of public health at Ohio State and Emory universities.

They conclude: “Careful analysis of all the data in context indicates that the net benefits of vaped nicotine products outweigh the feared harm to youth.”

Greater Impact on the Poor

The e-cigarette debate is about social justice as well as public health. Much of the outcry about vaping has come from well-educated, well-to-do, and well-connected parents who want to protect their kids. By contrast, the smokers who might benefit from switching to e-cigarettes, data shows, tend to be poor and less educated; people of color, especially Native Americans; gay or lesbian; homeless or incarcerated; and those with mental-health or other substance-abuse issues. They lack political clout.

RELATED CONTENT

Steven Schroeder, who as president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation from 1990 to 2002 led the philanthropy’s $700 million tobacco-control campaign, says much of the energy and money aimed at opposing e-cigarettes has come at the expense of curbing the use of smoked tobacco, which remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States.

The CDC estimates that cigarette smoking is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths a year in the United States — more than the number of deaths caused by Covid-19 during the first year of the epidemic.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s discouraging that smokers have fallen off the radar,” Schroeder says.

Different Approaches

The e-cigarette debate has fractured governments and nonprofits around the world. Australia, Brazil, and India have banned the sale of e-cigarettes.

By contrast, the British government actively promotes vaping as an alternative to smoking while discouraging use by young people. This strategy seems to be working: Use of e-cigarettes is largely confined to current and former smokers. Of the 3.2 million current vapers, just under 2 million are ex-smokers who have completely stopped.

Scientists are deeply divided. Each side accuses the other of distorting evidence.

“We are neck-deep in intractable, internecine warfare,” says Cliff Douglas, the former vice president for tobacco control at the American Cancer Society. “Like so much of our discourse these days, the debate has become polarized.” Young researchers have voiced concern about the amplification of one-sided, divisive views.

Harm-Reduction Debate

The challenge for foundations and nonprofits concerned about health is to act (or choose not to act) amidst contentious debate and scientific uncertainty. For now, virtually all of the philanthropic money driving the conversation — overwhelmingly from Bloomberg but also from the corporate foundation of the drugstore chain CVS -- has come down strongly against vaping.

Ethan Nadelman, founder and former executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, says: “There is now, essentially, no philanthropic funding to support harm reduction.”

The public-health strategy known as harm reduction is central to the e-cigarette debate. Simple in theory but controversial in practice, harm reduction aims to limit the dangers of risky behavior by offering safer, though not entirely safe, alternatives — clean needles or injection sites for intravenous drug users, contraception for teenagers who want to avoid pregnancies, and now e-cigarettes for smokers. Harm reduction can be useful when the evidence suggests, as it often does, that abstinence-only strategies like “just say no” don’t work.

ADVERTISEMENT

Steven Schroeder, who favors harm reduction, says: “The ideal solution for vaping would be to keep it out of the hands of kids and preserve it as a gateway for smokers who want to quit.”

Laws barring the sale of tobacco products to anyone under 21 should accomplish that. But the age limits are poorly enforced so the anti-tobacco nonprofits are determined to go beyond harm reduction to abolition — for better or worse.

SCOTT OLSON, GETTY IMAGES

Michael Bloomberg says Big Tobacco is trying to get young people hooked by selling e-cigarettes in flavors like cotton candy and gummy bear.

Fun, Freedom, and Sex Appeal

While people have been smoking or chewing tobacco for centuries, e-cigarettes are new. Most use a battery to heat a liquid that contains nicotine and flavors, creating a vapor that users inhale. They were brought to market in the early 2000s by a Chinese pharmacist whose father, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer.

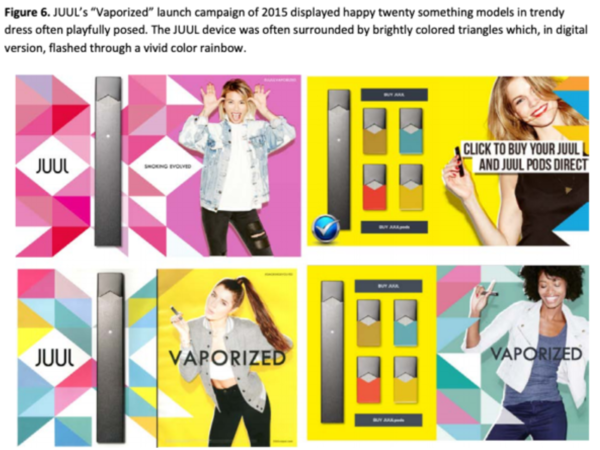

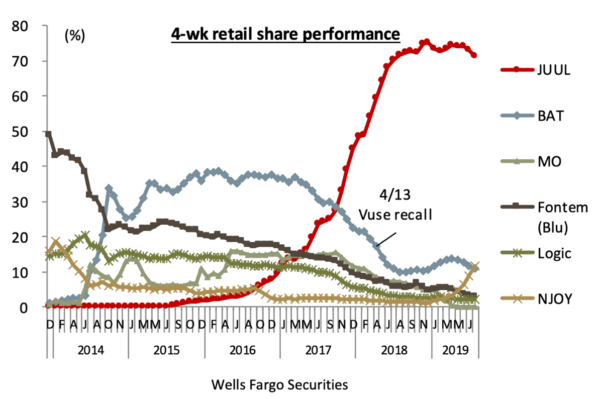

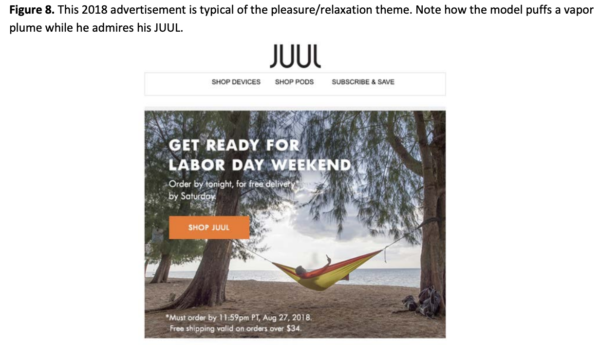

Vaping exploded in popularity in the United States with the 2015 launch of Juul, a company that bombarded young people with commercials associating its sleek pods with fun, freedom, and sex appeal. Juul, which loads up its pods with nicotine and delivers it rapidly to the bloodstream, became the market leader. Altria, the leading U.S. cigarette maker, bought 35 percent of Juul for $12.8 billion in 2018. To Myers of Tobacco-Free Kids, that was “a truly alarming development.”

By all accounts, Matt Myers is the most important voice in the tobacco-control movement. Tobacco-Free Kids, which is based in Washington, D.C., has about 140 staff members and a budget of $34 million, according to its most recent tax return. But it is Myers’s long history as an anti-tobacco crusader that gives him an outsize influence. A lawyer, Myers advised state attorneys general who sued tobacco companies during the 1990s, leading to the largest civil-litigation agreement in history, which transformed the anti-smoking movement.

Funds from the tobacco settlement endowed the Truth Initiative (formerly the American Legacy Foundation), which is also based in Washington. It is known for its award-winning anti-smoking commercials that over the years helped persuade millions of teenagers to avoid smoking. The Truth Initiative spends about $100 million a year on marketing, advocacy, and research.

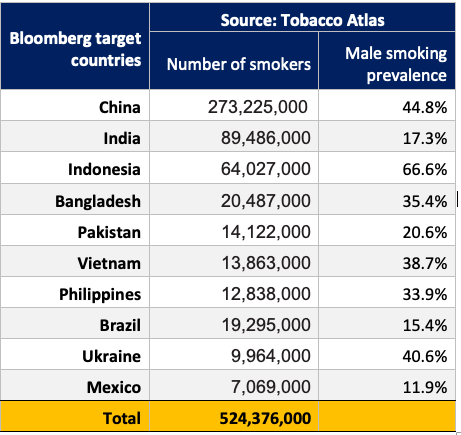

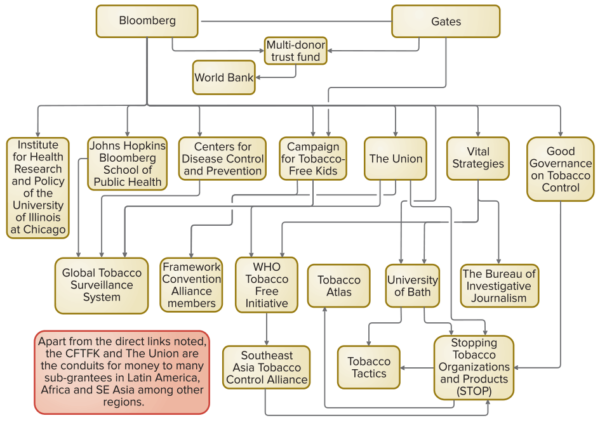

Michael Bloomberg, meantime, has been the tobacco-control movement’s most generous financial supporter, both as an individual and through his foundation. Bloomberg Philanthropies has committed nearly $1 billion to combating tobacco use worldwide, most of it focused on poor and middle-income countries. Bloomberg is also the largest individual donor to Johns Hopkins University, his alma mater, which named its school of public health after him, and as New York’s mayor, he was the leading advocate for a law banning smoking in restaurants and bars.

STEVE FORREST, PANOS PICTURES, REDUX

Michael Bloomberg’s philanthropy provided $160 million to end e-cigarette smoking. The billionaire has been active in tobacco-control efforts, including joining Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, head of the World Health Organization, at the 17th World Conference on Tobacco or Health.

The anti-smoking work funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation counts as a landmark philanthropic accomplishment. Cigarette smoking among U.S. adults fell to a low of 13.7 percent in 2018, down by more than two-thirds from its peak of 42 percent in 1964, which was the year the U.S. Surgeon General first warned of the health consequences of smoking. Globally, nearly two-thirds of the world’s population is protected by at least one comprehensive tobacco control policy, like cigarette taxes or package warnings, up from 15 percent when Bloomberg’s work began in 2007.

While smoking hit record lows, though, Myers, Bloomberg, and their allies worried about the growing popularity of e-cigarettes. In 2018, the FDA and the surgeon general declared youth e-cigarette use an epidemic.

“We had this dramatic increase in tobacco use among kids in the U.S. Really a huge public health crisis,” says Kelly Henning, a physician and epidemiologist who leads public health work at Bloomberg Philanthropies. “That was an alarm bell.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Anti-smoking charities that had cautiously recommended e-cigarettes as an alternative to smoking for people who can’t quit reversed themselves. The lung and heart associations and the cancer society all get grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies, either directly or through Tobacco-Free Kids.

The American Cancer Society, for example, used to advise visitors to its website that “switching to the exclusive use of e-cigarettes is preferable to continuing to smoke combustible products.” Now it says: “E-cigarettes should not be used to quit smoking.” The growth of vaping, coupled with the FDA’s failure to regulate e-cigarettes, caused the change, according to Laura Makaroff, a senior vice president at the Cancer Society.

The Truth Initiative, too, once embraced harm reduction. Its former board chairman, Tom Miller, Iowa’s long-serving attorney general, still argues that e-cigarettes are a “means to saving millions of lives.” Cheryl Healton, its former CEO, and David Abrams, formerly executive director of the Schroeder National Institute of Tobacco Research and Policy Studies, which is housed at the Truth Initiative, are harm-reduction advocates. So is Steven Schroeder, for whom the institute is named.

Why did the Truth Initiative decide to take a harder line? “As with everything we do, our work is led by the science,” says Robin Koval, CEO of the Truth Initiative. “We have an epidemic of young people vaping. We know from an emerging body of science that these products are far from harmless.”

Conflicting Claims

But just how harmful are they? Debates over the health effects of e-cigarettes are contentious. The Chronicle reviewed numerous studies and interviewed 30 scientists and activists to try to sort through conflicting claims. Remarkably, some scientists analyze the very same data and reach radically different conclusions.

Consider nicotine. “The big unanswered question is, is nicotine doing some harm to the [adolescent] brain,” says. Neal Benowitz, a professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco who is one of the world’s leading experts on the drug. “The concern is legitimate. Right now, we don’t know the answer.”

Other scientists, extrapolating from rodent studies, are more worried. “There’s no question that nicotine has negative effects on the developing brain,” says Rose Marie Robertson, a physician and the chief science officer of the American Heart Association. The State of California, in its guidance, is unequivocal, saying: “Simply put, nicotine is brain poison for youth.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Bloomberg, during an appearance on CBS News to discuss vaping, warned: “Just think if your kid was doing this and winds up with an IQ 10 or 15 points lower than he or she would have had for the rest of her life.”

This is, to be kind, a stretch. No reputable scientist believes that e-cigarettes cause a long-term drop in IQ. If nicotine caused sharp declines in intelligence, millions of smokers would have felt the impact.

“That is a good illustration of the danger of Bloomberg and his money,” says Clive Bates, the former director of the British nonprofit Action on Smoking and Health and a strong harm-reduction advocate. David Abrams, the former Truth Initiative scientist who is now a professor at NYU, says: “It’s never justified to distort or misinform the public, even in the service of trying to scare kids.”

FDA-approved nicotine-replacement therapies, after all, deliver nicotine in the form of gum, patches, sprays, or lozenges to smokers who want to quit. (In Britain, but not the United States, nicotine-replacement therapy is prescribed to pregnant women and children as young as 12.) It’s not the nicotine but the 7,000 or so other chemicals in cigarette smoke that cause disease and death, most experts say. Michael Russell, a British scientist and a pioneer of smoking-cessation treatments, famously said: “People smoke for nicotine, but they die from the tar.”

BRIAN SNYDER, REUTERS, NEWSCOM

In Massachusetts and elsewhere, the debate over e-cigarettes and their impact on young people, are flaring in state legislatures.

E-cigarettes, however, have not been approved by the FDA for tobacco cessation.

Stanton Glantz, formerly the Truth Initiative Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control at the University of California at San Francisco, says the negative impact of e-cigarettes goes way beyond nicotine. “For heart and lung disease, they’re about as bad as a cigarette. They might be worse for lung disease,” he says. A hero to anti-smoking activists, Glantz is one of the nation’s best known tobacco researchers.

Harm-reduction advocates don’t trust Glantz. Among other things, his 2019 federally funded study alleging that vaping doubles the rate of heart attacks had to be retracted when it turned out that some of the heart attacks took place before people started using e-cigarettes. The peer-reviewed study was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Many scientists share at least some of Glantz’s concerns. Laura Crotty Alexander, a physician and associate professor at the University of California at San Diego, had hoped that e-cigarettes could help her patients at a local VA hospital quit smoking. But as a mother of two, she’s grown concerned about young people and nicotine. “I’ve been surprised by the data that has come out showing that e-cigarettes are harmful,” she says. She supports a ban on flavored e-cigarettes, as does Jonathan Samet, a physician, epidemiologist and dean of the Colorado School of Public Health and longtime tobacco researcher. “We should be doing more science to address the uncertainties,” he says.

Rebellion and Experimentation

The anti-vaping forces and government agencies also worry that e-cigarette use today will lead to cigarette smoking in the future — that vaping functions as a gateway to smoking. Many studies show that young people who vape are more likely than their peers to go on to smoke and use illicit drugs.

The Truth Initiative says: “Young people who had ever used e-cigarettes had seven times higher odds of becoming smokers one year later compared with those who had never vaped.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The trouble is, studies that find an association between vaping and smoking reveal something about kids who vape — they’re more prone to experimentation or rebellion than their peers — but they do not establish a causal relationship between vaping and smoking. “If teens try one thing, they’re going to try other things,” says NYU’s David Abrams.

Population studies that track large numbers of young people cast doubt on the gateway theory. Smoking by high-school and middle-school students fell during the 2010s, the decade when more kids began to vape.

In a paper called “How to Think — Not Feel — About Tobacco Harm Reduction,” Kenneth Warner looked at a government-funded survey of smoking: “The year of the largest increase in e-cigarette use, 2013–14, saw the largest one-year percentage decline in high school seniors’ cigarette smoking prevalence (16.6%)” in the survey’s 40+ year history.”

Focus on Children

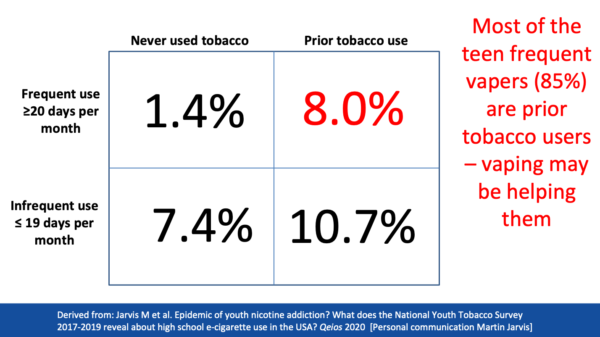

The two sides can’t even agree about whether the use of e-cigarettes by kids should be called an epidemic. A 2020 survey found that about one in five high-school students reported vaping in the previous month, but only about one in 15 frequently used e-cigarettes, the CDC says. Is that an epidemic?

Nuance was cast aside when Tobacco-Free Kids and its allies took their campaign to states and localities. They made Big Tobacco the enemy — that was easy after Altria bought a stake in Juul, which had aggressively marketed to teens — and they adapted a playbook developed during battles over tobacco taxes and laws prohibiting smoking in public places.

“Starting at the local level is always the best practice when it comes to tobacco-control policies,” says Cathy Calloway, director of state and local campaigns at the Cancer Action Network, the advocacy arm of the American Cancer Society. With a presence in every congressional district, the Cancer Society can “mobilize our grassroots volunteers and encourage them to contact their elected officials,” she says.

The anti-vaping campaign focused on kids. There are good scientific reasons to do so, explains John Pierce, a professor of public health at the University of California at San Diego who supports the work of Bloomberg and the nonprofits.

“It’s so hard to get people to quit,” Pierce says. It’s easier to get people not to start,” says Pierce.

ADVERTISEMENT

Politically, too, focusing on kids was smart. “There’s a fear of harming kids, and especially those who are seen as pure,” says Lynn Kozlowski, a professor of community health at the University at Buffalo and a harm-reduction advocate.

“You can’t understate the significance of the youth-use problem,” says Myers. “The level of harm that we have seen to kids far outweighs any benefit to adult smokers that has been actually studied and documented.”

JOHN TLUMACKI, THE BOSTON GLOBE, GETTY IMAGES

Maura Healey, the Massachusetts attorney general, was joined by anti-vaping activists when she announced a lawsuit against e-cigarette makers. The state’s legislature was among the first in the nation to ban the sale of all flavored tobacco products.

‘Dubious Public Health’

In San Francisco, the political action committee formed to support bans on e-cigarettes in two citywide referenda was called San Francisco Kids vs. Big Tobacco.

Here again, Bloomberg flexed his financial muscles: He contributed $9.4 million of his own money to the San Francisco anti-vaping campaigns in 2018 and 2019, accounting for 84 percent of the money they raised. (The American Heart Association gave another $612,000.) The tobacco companies, led by Juul, spent far more, but they were soundly defeated twice at the polls.

The result? You can buy Marlboros or marijuana but not e-cigarettes in the city. That may be good politics, but it is “dubious public health,” says Steven Schroeder.

In Massachusetts, Tobacco-Free Kids gave about $300,000 to a Boston charity called Health Resources in Action that made grants to community organizations that serve Black, Latino, and LGBT people to push for a ban on all flavored tobacco products. Among other things, they distributed a 15-minute film called Black Lives/Black Lungs about the toll that tobacco takes on African Americans and built a website called Fight All Flavors, with the help of Tobacco-Free Kids.

“What started locally in Boston accelerated quickly,” Kathleen McCabe, a managing director at Health Resources in Action, which fought for local and state laws. “I don’t think any of us anticipated how quickly the law was going to pass,” she said. Last June, Massachusetts became the first state to end the sale of all flavored tobacco products.

ADVERTISEMENT

What happened next should not have come as a surprise. Sales of tobacco products fell sharply in Massachusetts — by about 24 percent, judging by tobacco tax receipts — while tobacco sales grew in all five neighboring states. It’s too soon to know for sure, but “early signs indicate that the ban will not decrease tobacco consumption in the state,” says Ulrik Boesen, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation.

In Minnesota, which was one of the first states to impose a steep tax on vaping, the consequences create additional cause for concern. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that declines in smoking leveled off after imposition of the tax. The authors wrote: “The e-cigarette tax increased adult smoking and reduced smoking cessation in Minnesota.”

Harm-reduction advocates say they are starting to see similar trends across the United States. In an article headlined “Smoking’s Long Decline Is Over,” the Wall Street Journal reported that cigarette sales, which had been declining slowly but consistently, were flat in 2020. It’s impossible to know precisely what halted the decline — Covid-19 surely played a role — but some e-cigarette users probably returned to combustible cigarettes “because of increased e-cigarette taxes, bans on flavored vaping products, and confusion about the health effects of vaping,” the Journal reported.

Most people believe, erroneously, that vaping is as dangerous or more dangerous than smoking, surveys show.

David Sweanor, a lawyer based in Ottawa, Canada, who has worked globally for nearly 40 years at reducing tobacco’s health toll, including by suing cigarette companies, has been warning that the concerted efforts to demonize vaping have created a moral panic.

“The inevitable result,” Sweanor says, “is that it is more likely that smokers will stick with deadly combustibles, more vapers will revert to smoking, smoking will decline more slowly than it otherwise would, and the lucrative cigarette trade will have again been protected from a disruptive threat.”

He calls the anti-vaping nonprofits Big Tobacco’s Little Helpers.

Correction: This article has been updated to fix the attribution of a quote. The State of California, not Tobacco-Free Kids, said “Simply put, nicotine is brain poison for youth.”

We welcome your thoughts and questions about this article. Please email the editors or submit a letter for publication.

FOUNDATION GIVING

Marc Gunther

Marc Gunther is a veteran journalist, speaker, and writer who reported on business and sustainability for many years. Since 2015, he has been writing about foundations, nonprofits and global development on his blog, Nonprofit Chronicles.

This first post is the original news article as it appeared, the second post is the news article response from the Bloomberg crowd and the third post is the anti counter news article response back to the Bloomberg crowd basically telling them they have have no idea what their talking about with actual facts presented and to stop lying to all of us. Priceless!

https://web.archive.org/web/2021032...gainst-vaping-could-it-do-more-harm-than-good

Bloomberg’s Millions Funded an Effective Campaign Against Vaping. Could It Do More Harm Than Good?

Public-health experts say that e-cigarettes play an important role in getting people to stop smoking.

STEVEN SENNE, AP

The widespread use of e-cigarettes by teenagers declined after a campaign led by Michael Bloomberg and Tobacco-Free Campaign Kids.

GIVING

By Marc Gunther

MARCH 23, 2021

In September 2019, Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire philanthropist, and Matthew Myers, president of the nonprofit Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, unveiled a $160 million, three-year campaign to end what they described as an epidemic of e-cigarette use among kids.

In a New York Times op-ed, Bloomberg and Myers attacked Big Tobacco for putting young people in serious danger by hooking them on addictive e-cigarettes, which are sold in kid-friendly flavors like cotton candy and gummy bear.

Backed by a coalition of influential nonprofits, including the anti-tobacco Truth Initiative, American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, and American Lung Association, they called for a national ban on flavored e-cigarettes.

Bloomberg lamented: “All the progress that we’ve made in reducing teen smoking is being turned around.”

Their timing was propitious. A year earlier, the FDA and the U.S. Surgeon General declared youth e-cigarette use an epidemic. Fears were mounting about unexplained deaths linked to vaping. A few cities, including San Francisco, had banned flavored e-cigarettes. Michigan had just become the first state to do so.

What Philanthropy Is Accomplishing

This is part of a Chronicle series taking a deep dive into the results of big philanthropic efforts to discover what has worked, what has failed, and what donors can learn.

In the months that followed, five more states — California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island — banned flavored e-cigarettes. So did several big cities, including Chicago and Philadelphia. Congress raised the federal minimum age of sale for all tobacco products from 18 to 21. Anti-vaping messages dominated the national conversation.

All of this had an impact: The use of e-cigarettes by middle-school and high-school students declined sharply from 2019 to 2020, reversing previous trends, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I think it’s fair to say that Bloomberg’s funding has produced measurable, significant results,” says Myers, a founder of Tobacco-Free Kids and a longtime leader in the fight to curb tobacco use.

Seen in that light, the work of Bloomberg Philanthropies and Tobacco-Free Kids looks to be an uncomplicated story of philanthropic success.

It is anything but.

Bloomberg Philanthropies used its money and influence to curb vaping, to be sure. But others who have worked for decades to reduce deaths from smoking say the ongoing campaign against e-cigarettes is misguided, built on unsound science and likely to do more harm than good.

Less Dangerous

Kenneth Warner cares about tobacco control as much as anyone. A founding board member of the Truth Initiative — the nonprofit public-health organization committed to ending tobacco use — Warner has also been the president of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, the senior scientific editor of the 25th-anniversary Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health, and the dean of the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Kenneth Warner, a University of Michigan scholar, says harm from tobacco is far greater than from vaping: “Michael Bloomberg had sone great things for public health, but he is way off base on this.”

Years ago, Warner and a colleague, David Mendez, built a computer model that tracks the U.S. adult population’s smoking status and smoking-related deaths. When they ran data about vaping through the model, they found that under all but the very worst-case assumptions, the benefits of e-cigarettes, which can help smokers quit, exceed their costs in terms of lives saved. Warner says the campaigns against e-cigarettes are a mistake.

“Michael Bloomberg has done great things for public health,” he says. “But he is way off base on this.” Other respected elders of the tobacco-control movement share that view.

The critics’ argument goes like this: While e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco both contain nicotine, an addictive chemical stimulant derived from tobacco, e-cigarettes are much less dangerous than smoking. Vaping appeals to smokers who want to quit but need a nicotine fix. Like kids, adult vapers prefer flavors. So while no one wants teenagers to vape, removing flavored e-cigarettes from the market deprives adult smokers of a popular safer alternative.

ADVERTISEMENT

Worse, the critics say, by exaggerating the dangers of e-cigarettes, Bloomberg, Myers, and their allies have inadvertently given people a reason to smoke. Public opinion polls show that Americans overestimate the risks of vaping.

In “Evidence, Alarm and the Debate Over E-Cigarettes,” an essay in the journal Science, five public-health experts write that it’s a mistake to restrict access to vaping products while leaving deadly cigarettes on the market. The authors include Cheryl Healton, the former chief executive of the Truth Initiative, who is dean of the New York University school of public health, as well as the deans of the schools of public health at Ohio State and Emory universities.

They conclude: “Careful analysis of all the data in context indicates that the net benefits of vaped nicotine products outweigh the feared harm to youth.”

Greater Impact on the Poor

The e-cigarette debate is about social justice as well as public health. Much of the outcry about vaping has come from well-educated, well-to-do, and well-connected parents who want to protect their kids. By contrast, the smokers who might benefit from switching to e-cigarettes, data shows, tend to be poor and less educated; people of color, especially Native Americans; gay or lesbian; homeless or incarcerated; and those with mental-health or other substance-abuse issues. They lack political clout.

RELATED CONTENT

Steven Schroeder, who as president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation from 1990 to 2002 led the philanthropy’s $700 million tobacco-control campaign, says much of the energy and money aimed at opposing e-cigarettes has come at the expense of curbing the use of smoked tobacco, which remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States.

The CDC estimates that cigarette smoking is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths a year in the United States — more than the number of deaths caused by Covid-19 during the first year of the epidemic.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s discouraging that smokers have fallen off the radar,” Schroeder says.

Different Approaches

The e-cigarette debate has fractured governments and nonprofits around the world. Australia, Brazil, and India have banned the sale of e-cigarettes.

By contrast, the British government actively promotes vaping as an alternative to smoking while discouraging use by young people. This strategy seems to be working: Use of e-cigarettes is largely confined to current and former smokers. Of the 3.2 million current vapers, just under 2 million are ex-smokers who have completely stopped.

Scientists are deeply divided. Each side accuses the other of distorting evidence.

“We are neck-deep in intractable, internecine warfare,” says Cliff Douglas, the former vice president for tobacco control at the American Cancer Society. “Like so much of our discourse these days, the debate has become polarized.” Young researchers have voiced concern about the amplification of one-sided, divisive views.

Harm-Reduction Debate

The challenge for foundations and nonprofits concerned about health is to act (or choose not to act) amidst contentious debate and scientific uncertainty. For now, virtually all of the philanthropic money driving the conversation — overwhelmingly from Bloomberg but also from the corporate foundation of the drugstore chain CVS -- has come down strongly against vaping.

Ethan Nadelman, founder and former executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, says: “There is now, essentially, no philanthropic funding to support harm reduction.”

The public-health strategy known as harm reduction is central to the e-cigarette debate. Simple in theory but controversial in practice, harm reduction aims to limit the dangers of risky behavior by offering safer, though not entirely safe, alternatives — clean needles or injection sites for intravenous drug users, contraception for teenagers who want to avoid pregnancies, and now e-cigarettes for smokers. Harm reduction can be useful when the evidence suggests, as it often does, that abstinence-only strategies like “just say no” don’t work.

ADVERTISEMENT

Steven Schroeder, who favors harm reduction, says: “The ideal solution for vaping would be to keep it out of the hands of kids and preserve it as a gateway for smokers who want to quit.”

Laws barring the sale of tobacco products to anyone under 21 should accomplish that. But the age limits are poorly enforced so the anti-tobacco nonprofits are determined to go beyond harm reduction to abolition — for better or worse.

SCOTT OLSON, GETTY IMAGES

Michael Bloomberg says Big Tobacco is trying to get young people hooked by selling e-cigarettes in flavors like cotton candy and gummy bear.

Fun, Freedom, and Sex Appeal

While people have been smoking or chewing tobacco for centuries, e-cigarettes are new. Most use a battery to heat a liquid that contains nicotine and flavors, creating a vapor that users inhale. They were brought to market in the early 2000s by a Chinese pharmacist whose father, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer.

Vaping exploded in popularity in the United States with the 2015 launch of Juul, a company that bombarded young people with commercials associating its sleek pods with fun, freedom, and sex appeal. Juul, which loads up its pods with nicotine and delivers it rapidly to the bloodstream, became the market leader. Altria, the leading U.S. cigarette maker, bought 35 percent of Juul for $12.8 billion in 2018. To Myers of Tobacco-Free Kids, that was “a truly alarming development.”

By all accounts, Matt Myers is the most important voice in the tobacco-control movement. Tobacco-Free Kids, which is based in Washington, D.C., has about 140 staff members and a budget of $34 million, according to its most recent tax return. But it is Myers’s long history as an anti-tobacco crusader that gives him an outsize influence. A lawyer, Myers advised state attorneys general who sued tobacco companies during the 1990s, leading to the largest civil-litigation agreement in history, which transformed the anti-smoking movement.

Funds from the tobacco settlement endowed the Truth Initiative (formerly the American Legacy Foundation), which is also based in Washington. It is known for its award-winning anti-smoking commercials that over the years helped persuade millions of teenagers to avoid smoking. The Truth Initiative spends about $100 million a year on marketing, advocacy, and research.

Michael Bloomberg, meantime, has been the tobacco-control movement’s most generous financial supporter, both as an individual and through his foundation. Bloomberg Philanthropies has committed nearly $1 billion to combating tobacco use worldwide, most of it focused on poor and middle-income countries. Bloomberg is also the largest individual donor to Johns Hopkins University, his alma mater, which named its school of public health after him, and as New York’s mayor, he was the leading advocate for a law banning smoking in restaurants and bars.

STEVE FORREST, PANOS PICTURES, REDUX

Michael Bloomberg’s philanthropy provided $160 million to end e-cigarette smoking. The billionaire has been active in tobacco-control efforts, including joining Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, head of the World Health Organization, at the 17th World Conference on Tobacco or Health.

The anti-smoking work funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation counts as a landmark philanthropic accomplishment. Cigarette smoking among U.S. adults fell to a low of 13.7 percent in 2018, down by more than two-thirds from its peak of 42 percent in 1964, which was the year the U.S. Surgeon General first warned of the health consequences of smoking. Globally, nearly two-thirds of the world’s population is protected by at least one comprehensive tobacco control policy, like cigarette taxes or package warnings, up from 15 percent when Bloomberg’s work began in 2007.

While smoking hit record lows, though, Myers, Bloomberg, and their allies worried about the growing popularity of e-cigarettes. In 2018, the FDA and the surgeon general declared youth e-cigarette use an epidemic.

“We had this dramatic increase in tobacco use among kids in the U.S. Really a huge public health crisis,” says Kelly Henning, a physician and epidemiologist who leads public health work at Bloomberg Philanthropies. “That was an alarm bell.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Anti-smoking charities that had cautiously recommended e-cigarettes as an alternative to smoking for people who can’t quit reversed themselves. The lung and heart associations and the cancer society all get grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies, either directly or through Tobacco-Free Kids.

The American Cancer Society, for example, used to advise visitors to its website that “switching to the exclusive use of e-cigarettes is preferable to continuing to smoke combustible products.” Now it says: “E-cigarettes should not be used to quit smoking.” The growth of vaping, coupled with the FDA’s failure to regulate e-cigarettes, caused the change, according to Laura Makaroff, a senior vice president at the Cancer Society.

The Truth Initiative, too, once embraced harm reduction. Its former board chairman, Tom Miller, Iowa’s long-serving attorney general, still argues that e-cigarettes are a “means to saving millions of lives.” Cheryl Healton, its former CEO, and David Abrams, formerly executive director of the Schroeder National Institute of Tobacco Research and Policy Studies, which is housed at the Truth Initiative, are harm-reduction advocates. So is Steven Schroeder, for whom the institute is named.

Why did the Truth Initiative decide to take a harder line? “As with everything we do, our work is led by the science,” says Robin Koval, CEO of the Truth Initiative. “We have an epidemic of young people vaping. We know from an emerging body of science that these products are far from harmless.”

Conflicting Claims

But just how harmful are they? Debates over the health effects of e-cigarettes are contentious. The Chronicle reviewed numerous studies and interviewed 30 scientists and activists to try to sort through conflicting claims. Remarkably, some scientists analyze the very same data and reach radically different conclusions.

Consider nicotine. “The big unanswered question is, is nicotine doing some harm to the [adolescent] brain,” says. Neal Benowitz, a professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco who is one of the world’s leading experts on the drug. “The concern is legitimate. Right now, we don’t know the answer.”

Other scientists, extrapolating from rodent studies, are more worried. “There’s no question that nicotine has negative effects on the developing brain,” says Rose Marie Robertson, a physician and the chief science officer of the American Heart Association. The State of California, in its guidance, is unequivocal, saying: “Simply put, nicotine is brain poison for youth.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Bloomberg, during an appearance on CBS News to discuss vaping, warned: “Just think if your kid was doing this and winds up with an IQ 10 or 15 points lower than he or she would have had for the rest of her life.”

This is, to be kind, a stretch. No reputable scientist believes that e-cigarettes cause a long-term drop in IQ. If nicotine caused sharp declines in intelligence, millions of smokers would have felt the impact.

“That is a good illustration of the danger of Bloomberg and his money,” says Clive Bates, the former director of the British nonprofit Action on Smoking and Health and a strong harm-reduction advocate. David Abrams, the former Truth Initiative scientist who is now a professor at NYU, says: “It’s never justified to distort or misinform the public, even in the service of trying to scare kids.”

FDA-approved nicotine-replacement therapies, after all, deliver nicotine in the form of gum, patches, sprays, or lozenges to smokers who want to quit. (In Britain, but not the United States, nicotine-replacement therapy is prescribed to pregnant women and children as young as 12.) It’s not the nicotine but the 7,000 or so other chemicals in cigarette smoke that cause disease and death, most experts say. Michael Russell, a British scientist and a pioneer of smoking-cessation treatments, famously said: “People smoke for nicotine, but they die from the tar.”

BRIAN SNYDER, REUTERS, NEWSCOM

In Massachusetts and elsewhere, the debate over e-cigarettes and their impact on young people, are flaring in state legislatures.

E-cigarettes, however, have not been approved by the FDA for tobacco cessation.

Stanton Glantz, formerly the Truth Initiative Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control at the University of California at San Francisco, says the negative impact of e-cigarettes goes way beyond nicotine. “For heart and lung disease, they’re about as bad as a cigarette. They might be worse for lung disease,” he says. A hero to anti-smoking activists, Glantz is one of the nation’s best known tobacco researchers.

Harm-reduction advocates don’t trust Glantz. Among other things, his 2019 federally funded study alleging that vaping doubles the rate of heart attacks had to be retracted when it turned out that some of the heart attacks took place before people started using e-cigarettes. The peer-reviewed study was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Many scientists share at least some of Glantz’s concerns. Laura Crotty Alexander, a physician and associate professor at the University of California at San Diego, had hoped that e-cigarettes could help her patients at a local VA hospital quit smoking. But as a mother of two, she’s grown concerned about young people and nicotine. “I’ve been surprised by the data that has come out showing that e-cigarettes are harmful,” she says. She supports a ban on flavored e-cigarettes, as does Jonathan Samet, a physician, epidemiologist and dean of the Colorado School of Public Health and longtime tobacco researcher. “We should be doing more science to address the uncertainties,” he says.

Rebellion and Experimentation

The anti-vaping forces and government agencies also worry that e-cigarette use today will lead to cigarette smoking in the future — that vaping functions as a gateway to smoking. Many studies show that young people who vape are more likely than their peers to go on to smoke and use illicit drugs.

The Truth Initiative says: “Young people who had ever used e-cigarettes had seven times higher odds of becoming smokers one year later compared with those who had never vaped.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The trouble is, studies that find an association between vaping and smoking reveal something about kids who vape — they’re more prone to experimentation or rebellion than their peers — but they do not establish a causal relationship between vaping and smoking. “If teens try one thing, they’re going to try other things,” says NYU’s David Abrams.

Population studies that track large numbers of young people cast doubt on the gateway theory. Smoking by high-school and middle-school students fell during the 2010s, the decade when more kids began to vape.

In a paper called “How to Think — Not Feel — About Tobacco Harm Reduction,” Kenneth Warner looked at a government-funded survey of smoking: “The year of the largest increase in e-cigarette use, 2013–14, saw the largest one-year percentage decline in high school seniors’ cigarette smoking prevalence (16.6%)” in the survey’s 40+ year history.”

Focus on Children

The two sides can’t even agree about whether the use of e-cigarettes by kids should be called an epidemic. A 2020 survey found that about one in five high-school students reported vaping in the previous month, but only about one in 15 frequently used e-cigarettes, the CDC says. Is that an epidemic?

Nuance was cast aside when Tobacco-Free Kids and its allies took their campaign to states and localities. They made Big Tobacco the enemy — that was easy after Altria bought a stake in Juul, which had aggressively marketed to teens — and they adapted a playbook developed during battles over tobacco taxes and laws prohibiting smoking in public places.

“Starting at the local level is always the best practice when it comes to tobacco-control policies,” says Cathy Calloway, director of state and local campaigns at the Cancer Action Network, the advocacy arm of the American Cancer Society. With a presence in every congressional district, the Cancer Society can “mobilize our grassroots volunteers and encourage them to contact their elected officials,” she says.

The anti-vaping campaign focused on kids. There are good scientific reasons to do so, explains John Pierce, a professor of public health at the University of California at San Diego who supports the work of Bloomberg and the nonprofits.

“It’s so hard to get people to quit,” Pierce says. It’s easier to get people not to start,” says Pierce.

ADVERTISEMENT

Politically, too, focusing on kids was smart. “There’s a fear of harming kids, and especially those who are seen as pure,” says Lynn Kozlowski, a professor of community health at the University at Buffalo and a harm-reduction advocate.

“You can’t understate the significance of the youth-use problem,” says Myers. “The level of harm that we have seen to kids far outweighs any benefit to adult smokers that has been actually studied and documented.”

JOHN TLUMACKI, THE BOSTON GLOBE, GETTY IMAGES

Maura Healey, the Massachusetts attorney general, was joined by anti-vaping activists when she announced a lawsuit against e-cigarette makers. The state’s legislature was among the first in the nation to ban the sale of all flavored tobacco products.

‘Dubious Public Health’

In San Francisco, the political action committee formed to support bans on e-cigarettes in two citywide referenda was called San Francisco Kids vs. Big Tobacco.

Here again, Bloomberg flexed his financial muscles: He contributed $9.4 million of his own money to the San Francisco anti-vaping campaigns in 2018 and 2019, accounting for 84 percent of the money they raised. (The American Heart Association gave another $612,000.) The tobacco companies, led by Juul, spent far more, but they were soundly defeated twice at the polls.

The result? You can buy Marlboros or marijuana but not e-cigarettes in the city. That may be good politics, but it is “dubious public health,” says Steven Schroeder.

In Massachusetts, Tobacco-Free Kids gave about $300,000 to a Boston charity called Health Resources in Action that made grants to community organizations that serve Black, Latino, and LGBT people to push for a ban on all flavored tobacco products. Among other things, they distributed a 15-minute film called Black Lives/Black Lungs about the toll that tobacco takes on African Americans and built a website called Fight All Flavors, with the help of Tobacco-Free Kids.

“What started locally in Boston accelerated quickly,” Kathleen McCabe, a managing director at Health Resources in Action, which fought for local and state laws. “I don’t think any of us anticipated how quickly the law was going to pass,” she said. Last June, Massachusetts became the first state to end the sale of all flavored tobacco products.

ADVERTISEMENT

What happened next should not have come as a surprise. Sales of tobacco products fell sharply in Massachusetts — by about 24 percent, judging by tobacco tax receipts — while tobacco sales grew in all five neighboring states. It’s too soon to know for sure, but “early signs indicate that the ban will not decrease tobacco consumption in the state,” says Ulrik Boesen, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation.

In Minnesota, which was one of the first states to impose a steep tax on vaping, the consequences create additional cause for concern. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that declines in smoking leveled off after imposition of the tax. The authors wrote: “The e-cigarette tax increased adult smoking and reduced smoking cessation in Minnesota.”

Harm-reduction advocates say they are starting to see similar trends across the United States. In an article headlined “Smoking’s Long Decline Is Over,” the Wall Street Journal reported that cigarette sales, which had been declining slowly but consistently, were flat in 2020. It’s impossible to know precisely what halted the decline — Covid-19 surely played a role — but some e-cigarette users probably returned to combustible cigarettes “because of increased e-cigarette taxes, bans on flavored vaping products, and confusion about the health effects of vaping,” the Journal reported.

Most people believe, erroneously, that vaping is as dangerous or more dangerous than smoking, surveys show.

David Sweanor, a lawyer based in Ottawa, Canada, who has worked globally for nearly 40 years at reducing tobacco’s health toll, including by suing cigarette companies, has been warning that the concerted efforts to demonize vaping have created a moral panic.

“The inevitable result,” Sweanor says, “is that it is more likely that smokers will stick with deadly combustibles, more vapers will revert to smoking, smoking will decline more slowly than it otherwise would, and the lucrative cigarette trade will have again been protected from a disruptive threat.”

He calls the anti-vaping nonprofits Big Tobacco’s Little Helpers.

Correction: This article has been updated to fix the attribution of a quote. The State of California, not Tobacco-Free Kids, said “Simply put, nicotine is brain poison for youth.”

We welcome your thoughts and questions about this article. Please email the editors or submit a letter for publication.

FOUNDATION GIVING

Marc Gunther

Marc Gunther is a veteran journalist, speaker, and writer who reported on business and sustainability for many years. Since 2015, he has been writing about foundations, nonprofits and global development on his blog, Nonprofit Chronicles.

Last edited: